The beginning of Tango’s silk

When visiting the northern part of Kyoto, the rattling noise of the weaving machines can be heard from nowhere. Especially between autumn and winter, as the saying goes, “do not forget your umbrella, even if you forget your lunchbox”, along with the damp climate, Tango has a lot of rain and snow. Thanks to this weather, Tango has been suitable for producing silk, as it prevents from yarns being cut easily due to dry air. In fact, there are evidences which show that Tango has been a village of fabric from a long time ago. During the Nara period, “Ashiginu”, a type of silk, was presented to Emperor Shoumu, as well as “Tango Seigou”, another type of silk, was noted in the “Teikin Ourai”, which is supposed to be a textbook from the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

When visiting the northern part of Kyoto, the rattling noise of the weaving machines can be heard from nowhere. Especially between autumn and winter, as the saying goes, “do not forget your umbrella, even if you forget your lunchbox”, along with the damp climate, Tango has a lot of rain and snow. Thanks to this weather, Tango has been suitable for producing silk, as it prevents from yarns being cut easily due to dry air. In fact, there are evidences which show that Tango has been a village of fabric from a long time ago. During the Nara period, “Ashiginu”, a type of silk, was presented to Emperor Shoumu, as well as “Tango Seigou”, another type of silk, was noted in the “Teikin Ourai”, which is supposed to be a textbook from the period of the Northern and Southern Dynasties.

The birth of “Tango Chirimen”.

Within the inland area of Tango, agriculture and fabric supported the lives of people, until silk called “Omeshi Chirimen” developed in the western part of Kyoto. After that, people faced crisis, due to the “Tango Seigou” silk being hardly sold and the continuous poor harvest. Chirimen features fine emboss called “shibo”, which creates a beautiful luster for the fabric. At the time, the technique was said to be strictly confidential. In such time, in order to help the people, Kinuya Saheiji from Mineyama (Kyotango-shi Mineyama-cho), prayed for fasting to the Sho-Kannon at the Zenjo-ji Temple, and continuously trained and studied at the western part of Kyoto. As a result, in 1720, he mastered his original style of Chirimen.

Within the inland area of Tango, agriculture and fabric supported the lives of people, until silk called “Omeshi Chirimen” developed in the western part of Kyoto. After that, people faced crisis, due to the “Tango Seigou” silk being hardly sold and the continuous poor harvest. Chirimen features fine emboss called “shibo”, which creates a beautiful luster for the fabric. At the time, the technique was said to be strictly confidential. In such time, in order to help the people, Kinuya Saheiji from Mineyama (Kyotango-shi Mineyama-cho), prayed for fasting to the Sho-Kannon at the Zenjo-ji Temple, and continuously trained and studied at the western part of Kyoto. As a result, in 1720, he mastered his original style of Chirimen.

Momen-ya Rokuemon from Kaya (Yosano-cho Ushirono region), sent Tegomeya Koemon from Kaya and Yamamotoya Sahee from Migochi (Yosano-cho Migochi region) to the west. In 1722, they brought back the technique for implementation. After these 4 men acquired the technique, they taught the people in their region without hesitation. Chirimen spread across the Tango area in an instant, and the people overcame the difficulties through their own effort to make full use of the new technique.

Momen-ya Rokuemon from Kaya (Yosano-cho Ushirono region), sent Tegomeya Koemon from Kaya and Yamamotoya Sahee from Migochi (Yosano-cho Migochi region) to the west. In 1722, they brought back the technique for implementation. After these 4 men acquired the technique, they taught the people in their region without hesitation. Chirimen spread across the Tango area in an instant, and the people overcame the difficulties through their own effort to make full use of the new technique.

The cityscape and culture nurtured by the “Tango Chirimen”.

Thanks to its feature of “shibo”, an elegant texture along with an excellent color development, “Tango Chirimen” became one of the representatives for Chirimen. It established itself as the material for kimono, dyed beautifully in the Yuzen style, and has been supporting our kimono culture ever since. People continuously made an effort on developing colorful patterns on fabrics, and improving the product quality, such as refining (the process of removing protein, sericin, covering the silk thread) within the area of production and establishing the inspection system. During Showa 30’s to 40’s, the textile industry marked its golden age, “gachaman”, and was said to make a profit of thousands by weaving (“gacha” representing the sound of weaving the machine, and “man” meaning thousands in Japanese). As well as the surrounding area which was promoting sericulture and silk reeling industry, Tango developed as a major silk production area, and greatly contributed to the development of the whole northern part of Kyoto.

Thanks to its feature of “shibo”, an elegant texture along with an excellent color development, “Tango Chirimen” became one of the representatives for Chirimen. It established itself as the material for kimono, dyed beautifully in the Yuzen style, and has been supporting our kimono culture ever since. People continuously made an effort on developing colorful patterns on fabrics, and improving the product quality, such as refining (the process of removing protein, sericin, covering the silk thread) within the area of production and establishing the inspection system. During Showa 30’s to 40’s, the textile industry marked its golden age, “gachaman”, and was said to make a profit of thousands by weaving (“gacha” representing the sound of weaving the machine, and “man” meaning thousands in Japanese). As well as the surrounding area which was promoting sericulture and silk reeling industry, Tango developed as a major silk production area, and greatly contributed to the development of the whole northern part of Kyoto.

Along with representing as one of the traditional industry of the area and supporting people’s everyday lives, “Tango Chirimen” has affected the region’s history and culture, and encouraged the city to become lively. Indeed, the traces of prosperity in the past can still be seen in the traditional entertainment.

Along with representing as one of the traditional industry of the area and supporting people’s everyday lives, “Tango Chirimen” has affected the region’s history and culture, and encouraged the city to become lively. Indeed, the traces of prosperity in the past can still be seen in the traditional entertainment.

Mineyama,Omiya, Amino, Yasaka (Kyotango-shi), was a major producing area for Tango Chirimen. The textile factories, with saw tooth-like rooftops, still remain, along with the row of houses of the typical buildings of this area, a combination of residence and factory, scattered about.

Mineyama,Omiya, Amino, Yasaka (Kyotango-shi), was a major producing area for Tango Chirimen. The textile factories, with saw tooth-like rooftops, still remain, along with the row of houses of the typical buildings of this area, a combination of residence and factory, scattered about.

Although the Edo period’s Mineyama was a small feudal, consisting of approximately 13,000 koku, “Tango Chirimen” enriched the feudal finance as a local specialty. Kotohira Shrine, established by the feudal lord Kyogoku family, flourished thanks to Chirimen. It has an enormous precinct, many Shinto shrines, a votive picture (ema) depicting the grand festival patrol in the Meiji period, and holds festivals with glamorous stalls even up till now. Inside the Konoshima Shrine’s precinct, it enshrines the god of sericulture. Thread merchants who supplied silk, the primary material for Chirimen, and the people working in the sericulture industry created this. Also, there is an unusual guardian cat, which is supposed to get rid of mice, the greatest enemy of sericulture. All of this shows how much the people cherished the gracefulness of silk and their effort to protect its culture.

Although the Edo period’s Mineyama was a small feudal, consisting of approximately 13,000 koku, “Tango Chirimen” enriched the feudal finance as a local specialty. Kotohira Shrine, established by the feudal lord Kyogoku family, flourished thanks to Chirimen. It has an enormous precinct, many Shinto shrines, a votive picture (ema) depicting the grand festival patrol in the Meiji period, and holds festivals with glamorous stalls even up till now. Inside the Konoshima Shrine’s precinct, it enshrines the god of sericulture. Thread merchants who supplied silk, the primary material for Chirimen, and the people working in the sericulture industry created this. Also, there is an unusual guardian cat, which is supposed to get rid of mice, the greatest enemy of sericulture. All of this shows how much the people cherished the gracefulness of silk and their effort to protect its culture.

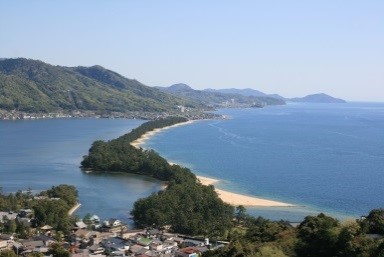

Miyazu, a castle town of Miyazu feudal, flourished during the Edo period, and was one of the producing areas of “Tango Chirimen” up until the end of Edo period. It became the circulation base of Chirimen shipment, mainly to Kyoto, and flourished as a commercial port city, with numerous merchants and sailors visiting. It even established a kagai, also known as a geisha district. Silks from all over the country, such as “Tango Chirimen” which circulated at the time, and the symbolic sceneries of the nearby Amanohashidate and Chion-ji Temple, which were visited by numerous Chirimen merchants, can be known from the folk songs passed down through the “Miyzazu Bushi”. Also, the luxurious parlors with beautiful white walls, merchant houses, such as a yarn seller, with a garden, and houses with lattice of evenly spaced vertical timber bars still remains. Indeed, all of these tell us the bustling atmosphere at the time.

Miyazu, a castle town of Miyazu feudal, flourished during the Edo period, and was one of the producing areas of “Tango Chirimen” up until the end of Edo period. It became the circulation base of Chirimen shipment, mainly to Kyoto, and flourished as a commercial port city, with numerous merchants and sailors visiting. It even established a kagai, also known as a geisha district. Silks from all over the country, such as “Tango Chirimen” which circulated at the time, and the symbolic sceneries of the nearby Amanohashidate and Chion-ji Temple, which were visited by numerous Chirimen merchants, can be known from the folk songs passed down through the “Miyzazu Bushi”. Also, the luxurious parlors with beautiful white walls, merchant houses, such as a yarn seller, with a garden, and houses with lattice of evenly spaced vertical timber bars still remains. Indeed, all of these tell us the bustling atmosphere at the time.

Kaya, Nodagawa, Iwataki (Yosano-cho), had rows of fabric houses and machine houses, which became the main producing area for “Tango Chirimen” at the beginning of the Showa period. Even more, Kaya and Nodagawa flourished as the circulation base for the “Tango Chirimen” when connecting Tango and Kyoto from the Meiji to the Showa period. There are buildings from the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa period, such as the fabric factory, “Nishiyama textile industry”, where the machine sounds can still be heard back from the Meiji period, and wooden houses, which reminds us of the circulation of Chirimen, lined across the street route of the gently curved slope. The “Chirimen Street” is like a roofless architect museum, with its beautifully maintained streets. The people in the city invest their money, created from the Chirimen production and circulation, into constructing roads, power plants, and railroads. In 1926, with the investment of the residents, “Kaya Railroad” opened. The flourishment of Chirimen at the time has been passed down as festivals, such as the Migochi Hikiyama event, which tours 12 glamorous portable shrine stalls, and the Ushirono, Sanjo, Kaya’s stall touring event.

Kaya, Nodagawa, Iwataki (Yosano-cho), had rows of fabric houses and machine houses, which became the main producing area for “Tango Chirimen” at the beginning of the Showa period. Even more, Kaya and Nodagawa flourished as the circulation base for the “Tango Chirimen” when connecting Tango and Kyoto from the Meiji to the Showa period. There are buildings from the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa period, such as the fabric factory, “Nishiyama textile industry”, where the machine sounds can still be heard back from the Meiji period, and wooden houses, which reminds us of the circulation of Chirimen, lined across the street route of the gently curved slope. The “Chirimen Street” is like a roofless architect museum, with its beautifully maintained streets. The people in the city invest their money, created from the Chirimen production and circulation, into constructing roads, power plants, and railroads. In 1926, with the investment of the residents, “Kaya Railroad” opened. The flourishment of Chirimen at the time has been passed down as festivals, such as the Migochi Hikiyama event, which tours 12 glamorous portable shrine stalls, and the Ushirono, Sanjo, Kaya’s stall touring event.

The technique and culture of “Tango Chirimen”, passed down even to today.

With its production of approximately 60% of Japan’s kimono material (for kimono, vindicate material) and consuming over 30% of the country’s silk, Tango region is still the largest silk producing area in Japan. The outstanding weaving technique of “Tango Chirimen” has been passed down, and has not only been used for making kimono, but with Western style clothing, scarfs, and interiors.

With its production of approximately 60% of Japan’s kimono material (for kimono, vindicate material) and consuming over 30% of the country’s silk, Tango region is still the largest silk producing area in Japan. The outstanding weaving technique of “Tango Chirimen” has been passed down, and has not only been used for making kimono, but with Western style clothing, scarfs, and interiors.

Also, the people are challenging themselves towards different fields, such as developing on hyper-silk processing technology, which hardly shrinks in wet conditions and is resistance to friction, and polyester Chirimen. The approximately 300 years of history and culture of “Tango Chirimen” has been passed down through the people’s constant effort, and will continue to ‘weave’ towards the future.

Also, the people are challenging themselves towards different fields, such as developing on hyper-silk processing technology, which hardly shrinks in wet conditions and is resistance to friction, and polyester Chirimen. The approximately 300 years of history and culture of “Tango Chirimen” has been passed down through the people’s constant effort, and will continue to ‘weave’ towards the future.

![Tango Chirimen corridor [Kyoto of the sea] - Japan inheritance](https://www.tangochirimen.jp/img/logo.png)